As the $90 trillion Great Wealth Transfer begins, millennials and Gen X aren’t just inheriting money. They’re being buried under an avalanche of baseball cards, fine china and collections of all sorts.

By Chris Rovzar, Bloomberg, November 14, 2025

Nick Malis knew that one day he would have to sort through the 10,000 Pez dispensers. For decades, he’d seen his mother collect them at stores and on eBay. She was a completist — she didn’t have one Bart Simpson Pez; she collected one in every color. They filled her pair of 2,000-square-foot rent-controlled lofts in SoHo.

And the Pez dispensers weren’t alone. They were arranged beside Holt Howard jelly jars, Russel Wright dinnerware, 1939 World’s Fair memorabilia, Popeye figurines and cartoon character bobbleheads on shelves she’d scavenged from New York City’s streets. Malis’ mother, Pepi Cammer, was an artist and graphic designer who’d done some work with Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, so there were decades’ worth of issues — including ones signed by Warhol and Truman Capote. She also had a range of antique corsets dating to 1791. “I grew up with a single mom who was almost a hoarderlike collector,” Malis says. “But it wasn’t stacks of newspapers. Almost everything was really good.”

In 2019, Cammer died after unexpected complications during surgery. Struck with grief, Malis was faced with leaving his home in Los Angeles, where he was a comedy writer, and going through the mass of stuff she’d accumulated — which also included her diaries, signed artworks by Keith Haring and Roy Lichtenstein, and some cocaine (complete with razors, mirrors, a scale and straws) left behind from the Studio 54 era.

Going through everything took him years.

Research firm Cerulli Associates estimates that over the next couple of decades, about $90 trillion in assets will be passed down from the Silent Generation and baby boomers to their Gen X and millennial heirs. Much has been written about the so-called Great Wealth Transfer and how it will change the global economy. A bigger mystery: What happens to all the physical possessions that will accompany that wealth?

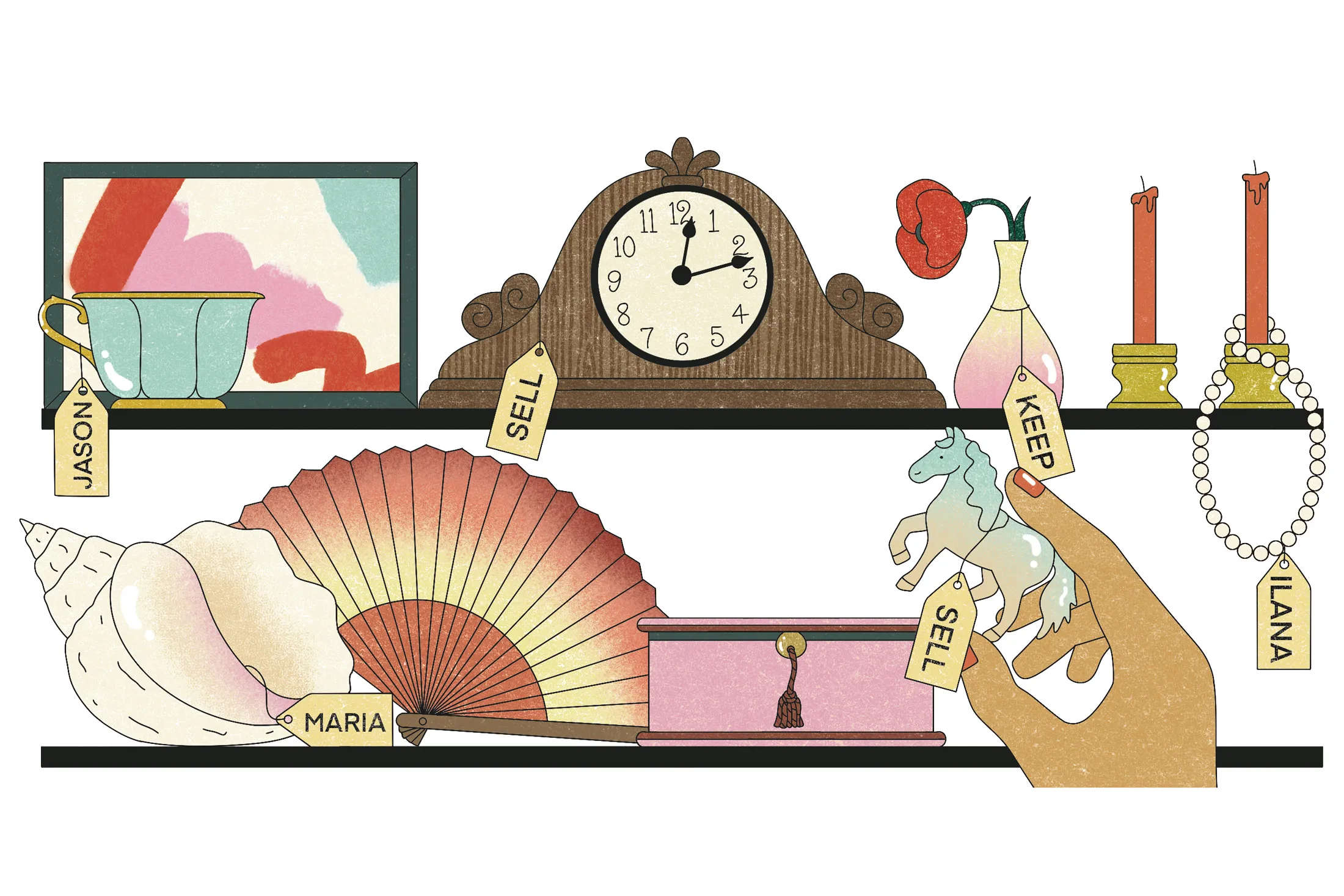

This has been dubbed “The Great Stuff Transfer,” and — oh, boy — is there a lot of stuff coming our way: silver flatware, antique wooden furniture, fine china, baseball cards, model trains, Hummel figurines, cut-crystal stemware and so, so many novelty salt and pepper shakers. Boomers are handling this prospect in a variety of ways. Some are trying to pass their special interests on to their kids, but others are getting rid of their belongings less sentimentally, so they themselves can downsize and avoid passing the buck. Many are ignoring the problem altogether.

This year my father surprised my brother and me by clearing out one of his most prized troves: his gun collection, gathered over almost 70 years. He had several dozen, from modern hunting rifles to handguns to Revolutionary War relics. He enjoyed having them, but he realized he was looking at them and oiling them, not using most of them — and that they might be frustrating for us to manage one day. He made a list with photos and told us to pick what we wanted. (I selected zero.) Then he decided what he’d keep for himself in his securely locked gun closet — we’ve nicknamed it the “Second Amendment Room” — and researched what the rest were worth. He sent out a call to dealers, and when someone offered him a fair price, he let the guy pick up the assortment from his home in rural Maine. I was impressed, and grateful.

Speak to almost anyone in their 30s, 40s or 50s, and you’ll find they have plenty to say about how they are having to manage — or are preparing to manage — their parents’ belongings. I recently polled my peers about this on Instagram and received dozens of emotional responses. “Oomf, let me tell you,” was how they often began. Or “Hoooo boy. Cracks knuckles.” Tackling one’s parents’ stuff, whether they’re already gone or still around, can be upsetting, stressful and deeply sad, as well as enlightening, cathartic or outright shocking. In almost all cases, it’s a lot of hard work.

So how did we get here? Why is there so much of everything? “In the 19th century, there was the first real emergence of a middle class, and suddenly regular people could own a lot of things,” explains Fritz Karch, who was the longtime collecting editor at Martha Stewart Living and runs a New Jersey antique shop called the Tomato Factory. Back then, “there was a real sense of pride and care in owning fine objects and passing them down.”

In 1851, Tiffany & Co. began selling silver flatware to upwardly mobile American families, about the same time the tradition of giving wedding china proliferated, a modern successor of the dowry. It became common practice to display such household finery in a well-made wooden cabinet, alongside cut-crystal glassware (another newly booming American industry) and other manufactured treasures. The Second Industrial Revolution, which began in the 1870s, was creating a new class of managers, bureaucrats and skilled tradesman who could afford to buy more (and more beautiful) stuff than they strictly needed.

The Depression of the early 20th century endangered that middle class, saddling an entire generation with a persistent sense of scarcity. Things both precious and mundane were best stored to hedge against future duress, and throwing away a well-made object was anathema. Things were meant to be passed down. “Baby boomers have Depression-era parents,” says Valerie Green, the owner of Seattle’s Pivot Organizing LLC, which specializes in organizing homes and small offices. “That’s really hindbrain stuff. It’s programming from their youth.”

For many, collecting became a way to channel aspirations. “My dad was a collector. He had a lot of interest in hunting, fishing and horse racing,” says Pia Catton, a nonprofit arts worker in New York. “He didn’t have a lot of time to do the actual things.” Her father, Domenic Catton, passed away in 2018, leaving her and her brother with a vast array of horseback riding memorabilia, silver, guns and fishing gear.

Collectors also tend to involuntarily accumulate stuff. My mother-in-law started acquiring charming salt and pepper shakers in the 1970s after receiving a set as a wedding gift; now if a friend of hers sees a funny pair, they buy them for her. Her hoard has ballooned. Russell Frost, 78, in Kingsey Falls, Quebec, began collecting teacups in 1979, inspired by his grandmother. His hobby became so well known locally that if anyone came into some teacups, they’d sell them to him. Now he has 1,300. One of his sons has promised to keep the collection intact as a small museum in their farmhouse.

The digital age has changed our relationship to accumulating and owning things. Smartphones eliminate the need to keep boxes of old photos. Same-day delivery reduces the utility of holding on to nine different-size flashlights just in case. Streaming means DVD and vinyl collections are for true believers. And even though resale platforms and collectors’ websites make it easier than ever to find things, younger generations likely have fewer places to store stuff in the first place.

According to a 2025 study from the National Association of Realtors, 42% of all homebuyers in the past year were baby boomers. Millennials represented 29% and Gen Xers 24%. The median age of a homebuyer in the US is 38, whereas 20 years ago it was 31. No wonder young people now have an impulse to collect experiences over things. “Maybe they’ve been to the top of every mountain, or seen every concert by a pop star,” Karch says. Memories don’t take up room in a rented studio apartment.

An entire industry is building up to meet this moment. There are many businesses like Green’s in Seattle to help aging people downsize or sort through a lifetime’s worth of things. Set aside your visions from TV shows such as Hoarders, which focused on people trapped by mental-health issues, or Marie Kondo’s Tidying Up, which featured an angel-faced cleaning expert applying her one-size-fits-all approach to every situation. These organizers are intuitive and apply different tactics to varying circumstances. They know where to start, how to categorize, where to sell or dispose of things, and how to calm your nerves through the whole process.

“We’re sort of like the gay uncles that come in and say, ‘No, you really don’t need that,’ ” says Cole Burden of SimplifyNYC, a company he started in 2019 with his husband, Caleb Dicke, to focus on what they call “generational decluttering.” They and others like them zero in on three things: getting rid of stuff, providing organizational tools and cleaning homes. “We really are facilitating the relationship between one generation and the next,” Burden explains.

Simplify, whose rates start at $100 an hour, has frameworks like the two-year rule: If you haven’t touched something in two years, do you really need it? They know how to navigate the stigma around accumulation and disorder and help families focus on the positive: “What do we love here that we want to keep?” Rather than: “Why did you keep all this junk?”

If it sounds a little like therapy, that’s because it is. “There is a lot of shame for people who find their stuff has somehow gotten out of control,” Green says. Organizing and decluttering is “something you’re supposed to be able to do, like cleaning,” she notes. “But no one’s taught us how to actually do it.”

The confounding complexity of the Great Stuff Transfer is that it encompasses everything from junk to sentimental items with little cash upside to treasures that are potentially quite valuable. Fine china, silver and antique furniture get a bad rap for being unwanted now, but there remains a fervent group of buyers looking to purchase the highest-quality version of each. You need to find the proper tools to figure out what’s what.

“We’re sort of like the gay uncles that come in and say, ‘No, you really don’t need that.’”

Take baseball cards. Aficionados call the period from about 1986 to 1994 the “junk wax era,” when companies churned out way too many cards. But if a collection is from the ’50s and ’60s or the late ’90s and after, there could be some pricey stuff there. The sports memorabilia and pop culture authenticating company PSA has a mobile app that rates the condition of your cards from photos and offers a pricing tool. It will even show your collection to professional traders and link you with eBay to sell.

“If folks are inheriting collections their parents in the baby boomer generation collected — ’50s and ’60s stuff — that is still considered relatively rare, especially if it’s in good condition,” explains PSA President Ryan Hoge, who notes there’s been a big increase in his business since 2018, when many sneakerheads transitioned into collecting NBA trading cards — and then baseball and other types of cards. (This year alone, card prices for Pokémon are up 54%, Star Wars 19% and baseball 15%.)

In other words, not only are there places to sell good stuff, but there are also people who still actively collect it. Young people, even! Sneakers, watches, handbags, vintage clothing and jewelry are much bigger markets today than they’ve ever been. That’s in part because when Gen Z splurges on a luxury item, they expect it to hold value and be salable in the future. The sneaker resale industry was less than $1 billion 10 years ago; it’s expected to reach $30 billion by 2030.

Underneath the logistics lies grief. It’s an emotionally complex experience processing an estate while mourning the loss of a loved one. Anderson Cooper recounts this beautifully in his podcast All There Is, which begins with him sorting through generations’ worth of treasures he inherited from his mother, Gloria Vanderbilt. “I was reading Marie Kondo, and her whole thing is keep only things that bring you joy. But so much of this stuff, it’s so my mom, that I feel like not keeping it is like throwing her memory away,” Cooper says in the first episode. He comes to realize that his mom would have wanted him to honor her by looking at her things and then moving forward with his own life.

A theme that comes through the podcast is that going through a meticulous assemblage can be joyful too. A person’s relationship with things can tell the story of a life. “While my mother was alive, it would always be frustrating to me that there was endless amounts of stuff,” Malis says. “But then as I went through it, I saw a lot of the stuff was incredible, and she had an amazing eye. That was really my inheritance.” As he sorted through it, he began posting his findings on social media. “People would love to see it all on my Instagram. It did a lot of work to repair whatever frustrating relationship I had with my mom,” he says.

Cammer had intended to sort through things for her son, but she passed away too soon. He found notes explaining what many things were and what to do with them. “It helped me understand her and reminded me of what a brilliant, funny, lively person she was,” he says. “I realized the Pez made her happy.”

Source: Chris Rovzar, Bloomberg, November 14, 2025

One thought